Change over time is a conceptual challenge in any historical gazetteer. At this preliminary stage, the periodization requirements of the Ottoman gazetteer are relatively straightforward. I aim to represent changes in the Ottoman administrations’s understanding of the hierarchical organization of its territory. I do not seek to understand the duration and extent of Ottoman control in practice. I merely wish to record the approximate date on which each territorial unit was established by the administration. I will assume that the unit remained in place until it was superseded by a new one. Thus the dataset is periodized using start dates, and its end dates are derived from the start dates of any subsequent designation of the place in question.

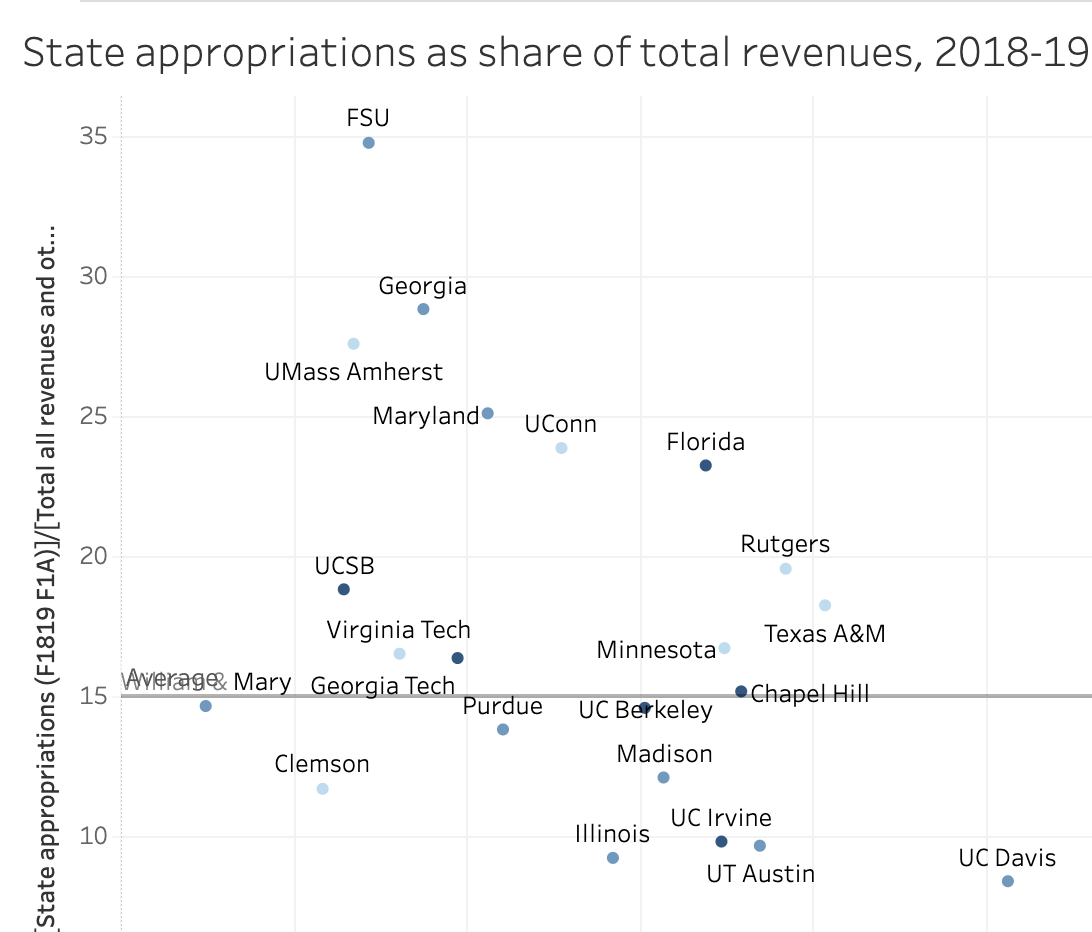

This chart shows the distribution of dates in Sezen’s “Osmanlı Yer Adları”:

The chart is responsive, so you can navigate its contents. Obviously, many of Sezen’s dates are post-Ottoman. Before the establishment of the Turkish Republic, the early 16th century and the mid to late 19th century are the periods with the largest number of place attestations.

Sezen’s dates are of four types (all expressed in the Gregorian calendar):

- Years (n=7445)

- Approximate years (designated by a

~, perhaps indicating mathematical translation into the Gregorian calendar; n=1090) - Centuries (for instance, 16 yy.; n=585)

- Ranges (typically with two years given, e.g. 1541-1686, but sometimes only a terminal year, e.g. “1926 yılına kadar”; sometimes the date range refers to a century rather than a year; n=99)

I’ve retained the raw dates as they appear in Sezen, except for date ranges, which I’ve transposed into start and stop dates.

With 534 different values, in four formats, it’s not immediately obvious how to ingest these dates into the Ottoman gazetteer. There are other reasons as well to think carefully about standardization. Sezen does not record the source(s) of his data, thus all of his dates must be considered provisional until confirmed with direct evidence. The dates revealed by that evidence will rarely be Gregorian, making Sezen’s data still more liable to adjustment.

As an alternative dating mechanism, I’m mapping Sezens dates onto the periodization of the Ottoman dynasty. This will allow the clustering of administrative changes under the reigns of the various sultans, a periodization that may engage the historiography more readily than the raw year counts.

To do this, I’m using a new Linked Data tool called PeriodO that “eases the task of linking among datasets that define periods differently.” I’ve used the chronology of sultans in Clifford Edmund Bosworth’s The new Islamic dynasties : a chronological and genealogical manual(2014). The dates and their links can be found on PeriodO.

Bosworth’s solution to the problem of calendar conversion was simply to record the first Gregorian year that corresponded to the Hijri year in which each sultan came to power. In the notes field of each sultan’s record, I’ve recorded the Hijri date of ascent that I found on Wikipedia.

I’ve used a few shortcuts to map Sezen’s dates onto the sultans’ reigns. I used approximate dates (~) as exact dates, mapped centuries to the sultan with the longest reign near the mid-point of the century, and used the first year of any date range as the mapping date. I mapped all years of transition (1876, for example) to the sultan whose reign began in that year. All dates after 1923 are assigned to the Turkish Republic (for which I’ve not yet established periods on PeriodO).

Obviously, this periodization scheme is a bit rough at the moment. Nevertheless, it should offer a general sense of the Ottoman territorial administrative structure over time. As more precise tools and data emerges, we can refine the Gazetteer.